Wednesday, October 22, 2014

5:00 am.

My alarm went off and I headed down to the kitchen. On this morning, uncharacteristically, I would be up before Carol. Normally, she has already made the pot of oatmeal and the pot of coffee by the time I get up, but this day I have a long day ahead and I am starting early. While the water for the oatmeal and coffee is boiling, I fry a couple eggs, thanks to our chickens who yesterday left us six fresh ones. I go to one of the charging stations (because our electricity gets turned on and off and has spikes, we only plug electronics into surge-suppressors) and retrieve my tablet and laptop, eventually to be put in my bag for the day, but initially to spend some time in "Seeking God's Face," a great prayer guide that I am trying to work back into my routine after watching my devotional discipline get inconsistent through all the transition of this summer.

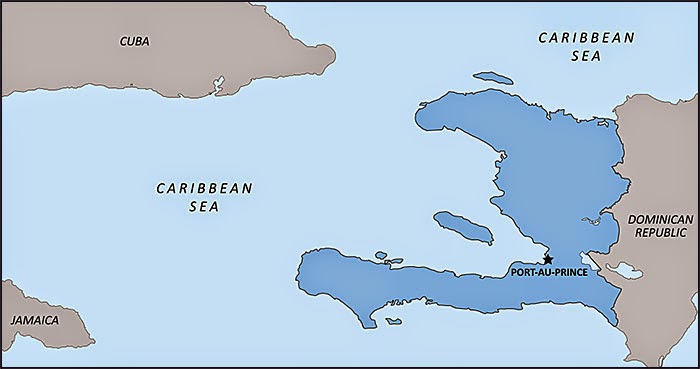

After eggs, oatmeal, one cup of coffee, a shower, and all my allergy and breathing medications, I am standing outside our house but inside our compound, waiting for my ride, slated to come for 6:30 am. At 7:00, my ride arrives, 30 minutes late being no big deal in a country where traffic and fatigue wreak havoc with schedules. I take the wheelchair which has been in my front hall for the night and place it in the back of Nelson's 4x4 pick-up truck. Lunise and Nelson are in the front buckets. They both work for World Renew; Lunise is the head of the team and Nelson does his work primarily in the Leogane region, for those who remember: the epicenter of the earthquake almost five years ago. I squeeze my 6'1" frame into the back of the Nissan quad-cab. It's going to be a long 3-1/2 hour drive, though we will only cover about 80 kilometres (50 miles). At 6:30, the temperature is already 25 celsius and the heat index by afternoon should be in the low 40's. Mercifully the pick-up truck has air conditioning. As a bonus, it seems to be working.

We wind our way through the craze and maze of streets that is Port-au-Prince. Since the city is built against the side of a mountain range, there is no shortage of steep grades. And where the roads are not paved, you can bet that rain storms have carved crevices into crevasses, making a backseat passenger wonder how we will get down (or up) the next hill. This will prove to get even more interesting as we near our mountainous destination in a few hours.

En route to our destination we make our way through the downtown of Port-au-Prince, including a massive street side fish market, jammed with a sea of antiquated rusty residential freezers and broken camping coolers, holding the catch of the day, or week, or month. It's hard to know. There is no packaging or code dates. Rather than meat inspectors and butchers in white coats, there are vendors, mostly weathered women with vacant stares, sitting on boxes, blocks, or crates. Fish aren't the only things for sale today, or any day. Among the many products splayed out on sidewalks each morning are charcoal bricks, phone chords, jeans, t-shirts, mangos, papaya, avocado, plantains, bread, sneakers, propane, bags of water, and a host of other things. One person commented the other day that Haiti is the only place you can buy a goat and a prom dress from the same vendor. Information overload is starting to set in after just an hour and all I am doing is looking out the side window.

Looking out the front window produces considerably more stress. Sometimes the stress is because of oncoming traffic. The road is usually 2 lanes, one each way. I say usually because the meandering width of the road is reminiscent of the lines on my lawn when I mow absentmindedly. Sometimes the road is exceptionally wide; other times and it is clearly not wide enough to accommodate oncoming traffic. So, the view through the windshield often looks frighteningly similar to what one would imagine a head-on collision might look like just before the collision. In addition, Nelson is a confident driver, willing to pass on a curve, up a hill, pretty much anytime, including times there IS oncoming traffic. For that he lays on the horn and creates the third (center) lane that becomes our safety zone. Other times the stress comes from wondering whether the truck in front of us will lose its load. At one point we were trailing behind a flat-bed truck carrying bags of rice, seven layers high. The first four layers looked to be tied down with ropes from the bag and sides. The top three rows of rice bags though were simply loaded on top. In addition, there were half a dozen people sitting up top of the rice bags. While travelling behind a load like this, you can't help but make mental contingency plans of what to do if the whole load comes loose, even if you are sitting in the back seat. My heart rate imperceptibly creeps higher.

In Carrefour, the city just west of Port-au-Prince on the north shore of Haiti's southern arm, we stop to pick up Paste Ernst. Ernst works for PWOFOD, a ministry which does diaconal development. Ernst is a man I met a few days ago as we began this week-long evaluation of MDK, an impressive leadership development network that is proving itself through tangible results. When I met Ernst, still practicing my Creole, I asked about his work and about his family. He spoke slowly so that I could string together what he was saying. Most of the words, I was finding, were actually within my vocabulary. However, one sentence, though I could understand the words, was packed with more meaning than words can contain. I had asked about his wife, wanting to know what she does. He replied, "Li kraze nan tranbleman de te a." "She was crushed in the earthquake." At the time Ernst and his wife were living in Leogane, the epicenter of the January 12, 2010 earthquake which snuffed out 200,000 wives, husbands, daughters and sons. On that day five years ago, I was with a team in the Dominican Republic, building a trade school. Ersnt, a pastor and father of five children, the youngest being three, was doing what too many people were doing: grieving and trying to move forward. Now, here he was five years later, not only raising five children but working with PWOFOD to raise up deacons and giving a week of his time to help evaluate a ministry that is raising up other leaders. Though only 6' tall, he is a mountain of a man, despite what mountains of rubble have done to him.

Ernst and I sat in the back seat of the truck. As far as I could understand, we were at capacity, maybe beyond it with our knees digging into the seat backs in front of us. I continued to look through the front windshield to ensure we would miss yet another head-on collision. The air was often clouded with dust from the street or pitch black smoke from a truck that hadn't had an oil change in decades. Dogs, vendors, school-children in bright pink, yellow, or green uniforms darted through and alongside the traffic. The view out the side window reminded me of the old Flintstones cartoons when Fred would be running through the house, repeatedly passing the same couch, same window, same table, then couch, window, table again. We passed an unending series of lotto shops (often with names like "Grace of God" or "Eternal Father"), meat vendors, soda markets, deep friers, shoe and clothing vendors, and dust-covered homes, often with someone out front doing the daily morning chore of sweeping the loose dirt off the packed dirt front step. Each scene was washing into the next with sights that three months ago were jarring and today were calmingly familiar.

About two hours into our trip, we were passing a gas station when a man shouted out, arms raised, "hey!" It was another member of our evaluation team, Jean Brenor, whom we had thought we were meeting at our destination. Here he was, waiting with another man along the side of the road, waving us down for a ride. Without even considering sardining themselves into the cab, both men, bags in hand, hopped into the back of the pick-up and sat on the side walls, holding onto a frame above the cab. Moments later we were again making our away along the sea-side road, although because of the shacks along the road blocking the view, the only hint of sea was the smell in the air and the occasional peak where a home had been demolished but not yet rebuilt.

We were on our way to Meye, a remote community in the mountains, halfway between Leogane and Jacmel. Meye is one of many towns in Haiti not only not on any map, but barely on any road. We began our ascent into the mountains along a main road, it was even paved. Winding its way up and around corners, our ride, mostly in low gear was a series of blind corners, horn blaring, and at least one back seat passenger in prayer. I envisioned, naively, that once we got to the top of the mountain things would level out and we could relax. I was wrong. The adventure was just beginning.

We turned off the main (read: paved) road and began our way along a dirt road. Now dirt roads in Canada are often flat, at least smooth, roads. Sometimes they have fresh gravel and sometimes they are two tracks. Maybe after a bad rainstorm they are 'washboarded' meaning they have bumps a few inches tall, lasting sometimes as much a few hundred metres when it is really bad. Canadian dirt roads would be luxuries here. Dirt roads in Haiti are exactly what you might expect in a place where road construction graders are virtually non-existent and where torrential rains carved new ditches - right down the middle of the road! This dirt road, though, made every other dirt road I had seen before look like a superhighway. Not only were the ruts in the road deep enough to make us continually stop our 4X4 to scout a route through much like a whitewater canoer would approach a set of Class IV rapids, but these rutted roads were narrow and winding around the edges of mountains with sheer drop-offs and no guard rails. All that would be enough to bring up breakfast, but to add to the fun, every once in a while there would be another 4x4 coming the other direction, sometimes forcing us to "take the outside lane" also known as the edge of the cliff while we passed one another. And again, just as we had seen them in the dusty streets of Port-au-Prince, so also along the remotest stretches of mountain edge road: children in bright school uniforms, the little girls amoung them sporting large white hair braids. Later that night, these sights would haunt my sleep as I continually dreamt I was falling off a mountain or into one of the ditches in the road.

Finally, we arrived in Meye, a tiny mountain village with a church and a Christian school right across the road from one another. We were there to meet with local leaders who had participated in a leadership training program, MDK (Ministry of Development for Christians). We were evaluating MDK as a ministry partner, wanting to be stewards of the funds God allows to flow through our hands en route to his purposes. To evaluate MDK, we were going out to the communities MDK was serving, asking questions like, "What did MDK teach? What do you remember? What did you put into practice? What obstacles did you face? and What has grown out of your implementing what you learned? There in the Meye church building, it was a joy to see 12 local leaders, 2 of whom were women, all actively taking part in the discussions. Using large white sheets of paper, they drew pictures of ways they have connected with other organizations. They were laughing and slapping one another's backs and when it was all done and we were ready to go, they were asking if we could leave the large pieces of white paper behind to help them dream and plan. We were all smiles.

|

| The chart on the left categorized what was learned, how they applied it and what resulted. The Venn Diagram on the right depicted the leadership development network (only 2 years old in this village) and its relationship to many organizations including churches of multiple denominations, Christian schools, government, and businesses. It was inspiring! |

Our smiles, however, paled in comparison to the smiles of one little girl in the village. I wrote above that I had put a wheelchair in the truck. It was for someone in Meye. MDK had initiated a ministry to serve many post earthquake victims who had lost legs, feet, or the use of either. They call the ministry, "Ban m' yon pye" which translates "Give me a foot." Not wanting to crowd around the girl, one of us, Jean Brenor, presented the girl with her new wheelchair. While she wouldn't be able to take it around town for lack of sidewalks or smooth surfaces, she would be able to use it around her home, at her church, and at school. It was powerful to see this tangible affect of MDK's work. MDK is developing leaders and those leaders are initiating and carrying out ministry and we were the privileged observers of the end result.

Another tangible result of the leadership development group was a bridge. Just down the hill from the village is a gulch. Gulches are the dry beds of what become raging rivers in raining season. While the gulch was walked through regularly by many going to and from the village in dry season, rainy season was cutting these folks off from their community, their church, and their sources of income. The leadership development network spawned an initiative that built a bridge. It's funny, in ministry I have often talked about building bridges, but they were always metaphorical -- between the church and community, between people who aren't connecting -- but here was a group literally building a physical bridge to connect people in a meaningful way.

Before we had left, the one long-term missionary in the village, Anelise, asked if we could bring her three empty propane cylinders back to Port-au-Prince to be filled. The propane cylinders were at least four, maybe five, feet long. The two who had been sitting in the back on the way up were glad to have these cylinders in the back of the truck with them since they could serve as seats to sit on as we made our way back down the mountain. Let's just say that it made the ride back down the mountain, at faster speeds going down than on the way up and now with three large propane tanks and just as many open air passengers, much more interesting than the ride up. Here's a few photos of the view on the way down.

|

| Heading north down the mountain toward Leogane. The Gulf of Gonaive is in the distance. |

|

| The picture doesn't quite capture it, but what the camera shows as a grassy hillside is actually a very steep drop-off. Notice the absence of guardrails and proximity of the edge. Then multiply it by 20 kilometres. Yeah, it was that kind of drive. |

A few conclusions or learnings from my day:

1. Leadership Development, when done well, leads tangible results as evidence of the Gospel propelling people to compassionate action on behalf of others. The wheelchair and the bridge are just two examples. I am inspired by my Haitian brothers and sisters to expect tangible results from leadership development. Though I am working on my doctorate on this same subject, I learned from these humble mountain-dwelling farmers.

2. Four-passenger Nissan Quad-Cab pickup trucks can hold seven people and a whole lot more.

3. Mountain driving can inspire both prayers of praise (for the incredible sights) and supplication (that you don't fall off the side of the mountain).

4. Missionaries need 4x4's. I can remember thinking before as an American and Canadian pastor, "Why do missionaries need 4X4's? Isn't that a little excessive, expense-wise?" Just a few months of experience here is teaching me that not only do missionaries need 4x4's to do their work, but that for a 4x4 to survive these driving conditions for any length of time in mileage or age is a small miracle in itself. It will be easy to give to missionary vehicle fundraisers in the future :).

5. Haiti is a beautiful place. Yes, it is jammed with poverty and chaos and too many ugly results of both, but it is a place of natural beauty, of a resilient, passionate people, and of church leaders who expect to not only speak the Gospel but to live it out for the sake of others.

Thanks for sending me here. It is my privilege to bear witness to what I see.

Time to put the empty tea-cup on the counter and get on with my day.

.JPG)

.JPG)